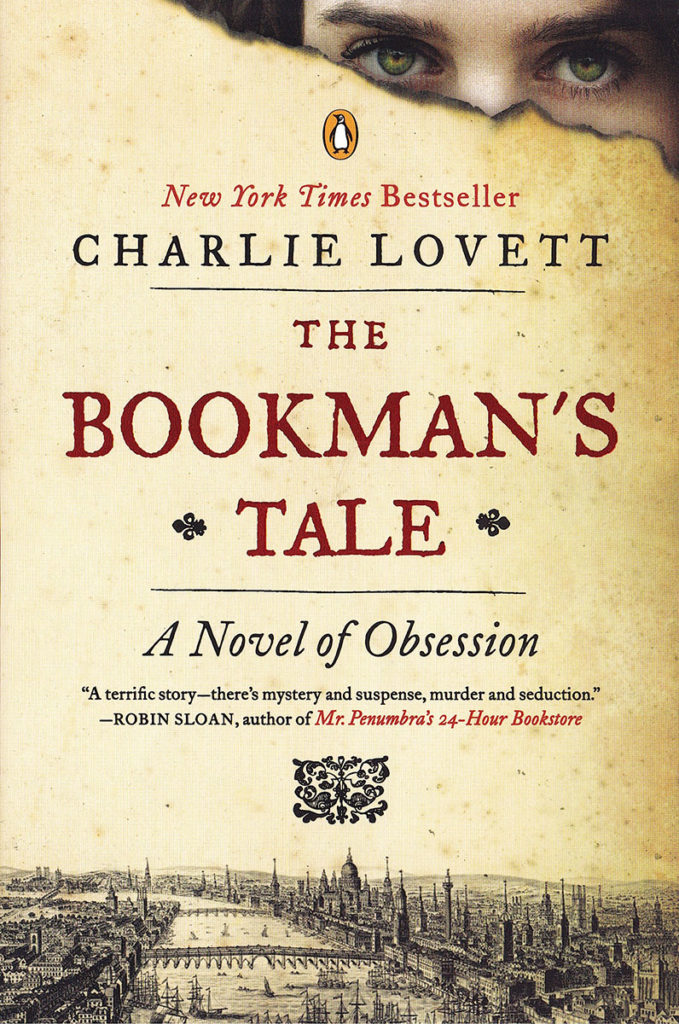

The Bookman’s Tale – Backstory

Some stories about the genesis of the book and how my writing passions grew out of rare books and the English countryside.

Some stories about the genesis of the book and how my writing passions grew out of rare books and the English countryside.

The First Idea

In 2005 I was walking alone in the Yorkshire countryside on a chilly day. I had just finished devouring the latest Harry Potter book and I was thinking about what I might like to write next when I hit on the idea of a hiding a secret in an old family chapel. I think this idea must have come from recalling a previous trip to the north of England during which some friends had taken me to see a tomb in just such a chapel. Like Evenlode House, the house near the chapel, once a fine country home, had fallen into disrepair and the residents lived in trailers in the garden. The chapel itself was covered with vines, but held a quite remarkable collection of Anglo Saxon carving along with the impressive medieval tomb of a local noble who had supposedly slain a dragon nearby. When I returned from my walk that day in 2005, I began to make notes and ended up with several pages of ideas about a Victorian English painter and a modern day American expatriate bookseller. With the exception of those two characters and the settings of the falling-down house and hidden chapel, almost nothing of my original notes made it into the novel. In fact, it was two years later before I started working on the book in earnest. By that time I had come up with the idea that the book would include three booksellers from three widely different time periods: Elizabethan, Victorian, and contemporary. Because I had been an antiquarian bookseller myself for several years, I knew a lot about the world in which the book was set. During the same time that I was working on revising the early drafts of the novel, my wife and I bought and renovated a cottage in the Oxfordshire village of Kingham—the same cottage we had lived in for six months ten years earlier. With a few modifications, our cottage became Peter’s cottage, and my own familiarity with Kingham and the English countryside (including places such as Hay-on-Wye which I had visited many times) helped me create the world of the novel.

Keen’s Cottage

In 1997, my wife Janice and I decided we wanted to live in England for six months—not as tourists, but as residents. Our daughter Jordan was nine, and we took her out of school and in January moved to the small Oxfordshire village of Kingham. We chose Kingham almost at random—I wanted to be close to Oxford so I could do some research on Lewis Carroll, but beyond that we simply chose a cottage that was available for a six-month rental and had the amenities we needed. Almost immediately we fell in love with Kingham—a peaceful village of 700 people close to the more famous tourist towns of the Cotswolds, but mostly undisturbed. We took our daughter to every Shakespeare play at the RSC and the Globe; we went to see nearly every show in the West End; we traveled to Scotland, Italy, Poland, and Amsterdam, as well as all over England. I was working on a book about the places Lewis Carroll had lived and worked, so we visited places from the Isle of Wight in the South to Whitby in the North. We rowed up the river from Oxford just like Lewis Carroll and Alice had done, and we made many friends among other Carroll enthusiasts. Most importantly for us, we met a wonderful family who lived at the end of our lane and became dear friends. In the years that followed we remained close with this family. We visited them in Kingham and they visited us in the USA. The parents even joined us on a rafting trip down the Grand Canyon, and we sang at their daughter’s wedding in Kingham. Then, in 2007, we received an e-mail from them telling us that Keen’s Cottage, the cottage we had rented ten years earlier, was for sale. We bought the cottage and, with the help of our friends’ eldest daughter, renovated it. Since then we have lived in Kingham for about six to eight weeks each year, and used the cottage as a rental property in our absence. We have had the joy of visits from family members and friends, with whom we’ve been able to share our peaceful corner of England. So, when the fictional Peter Byerly needed to be hiding away from the world in a quiet English village, I did not hesitate to put him in Kingham, and I let him be the owner of the fictional version of Keen’s Cottage. While the Kingham of the book is fictional (as are the houses Peter visits), the real Kingham is a lovely place full of kind and generous people. I like to think that Peter would have been completely at home there.

My Life as a Book Collector

When I was growing up, my father Robert Lovett began collecting editions of Robinson Crusoe. It’s a great novel to collect because it’s been in print constantly since 1719. Bob eventually donated his collection of over 700 English language editions to Emory University. As a teenager, when I began traveling on my own, I would troll through bookshops looking for copies to buy for him. I learned that I loved old books and also I liked the idea of collecting a single title. In college, I began to collect copies of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, inspired by an old set of records I used to listen to on a rainy day—Cyril Ritchard reading the Alice books. I had no idea what I was getting into, and certainly didn’t know what a fascinating person Lewis Carroll would turn out to be. Over the years my collection has broadened to include a wide array of books and other materials related to Lewis Carroll and his world. I have Alice translated into scores of languages, first editions of all of Carroll’s major works (including the extremely rare first edition of Alice—only five copies are in private hands), movies, plays, etc. etc. I’ve ended up writing several books about Carroll and these have spurred my collecting in new directions. Some of my favorite items are those you won’t find anywhere else—a seven foot tall theatre poster from the 1930s, copies of Alice and other books inscribed by the author, and even Lewis Carroll’s own 1888 Hammond typewriter. But my favorite thing about book collecting has been the people to whom it has introduced me—other Carroll enthusiasts, booksellers, auctioneers, and scholars. I’ve made friends around the world, and my shelves are full of books that come with wonderful stories of how I acquired them, often with the help of a new friend.

Holy Grails

Peter uses the term “Holy Grail” to refer to the ultimate acquisition for a book collector. I’ve been with groups of collectors who bandy this term about; “What’s you’re Holy Grail?” is a frequent question, meaning what book, more than any other, would you like to acquire. When I started collecting, my Holy Grail was the true first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Only twenty-two copies survive, and all but five of those are in museums or libraries. In 1986, I was lucky enough to buy one of those five at auction. Now my gut reaction to the question “What is your Holy Grail?” is not unlike Peter’s reaction: My Holy Grail is a book I don’t even know exists, some previously unknown work by Lewis Carroll. It may sound preposterous, but as recently as this past spring I discovered a previously unknown contribution that Lewis Carroll had made to a periodical in 1861. If I had to pick a “known” book for my Holy Grail, I suppose it would be one or all of the four missing volumes of Lewis Carroll’s diaries. These manuscript volumes went missing in the 1930s and cover an important time in Carroll’s life—he was learning to be a photographer, studying for his ordination, and growing the friendship between himself and the family of Henry George Liddell, including little Alice, his muse. But the great thing about Holy Grails is that every collector has a different one, and we get to learn about each other and our passions by sharing our dreams of grails with one another. I’m sure that anyone who loves English literature would love to stumble upon the grail that Peter finds.

Real Stories of Antiquarian Bookselling

The Bookman’s Tale deals in part with the fact that sometimes what flutters out from between the pages of a book, or what is written in the margins, is more valuable than the book itself. In my years as an antiquarian bookseller, I encountered this reality many times. Early in my career, a customer brought a box of books, including a set by Winston Churchill, into the shop where I was working. We bought the lot, but not until later when I was pricing the books did I discover, tucked between the pages of two of the Churchill volumes, a pair of handwritten letters by Winston Churchill himself. The customer was long gone, but needless to say the letters were worth far more than the books. Another time I bought an entire house full of books at an estate sale. I was sorting through them when I noticed a scrawl on the endpaper of a book I would have priced at $5 or $10 that looked like it said “William Faulkner.” I consulted an expert in southern literature and he confirmed that it was a rare Faulkner ownership signature. I sold the book with one phone call (and for a lot more than $10). Peter’s belief that even a house as dilapidated as Evenlode House might be home to some rare books is not entirely without precedent in my life. One time I was called out to appraise some books for an estate. When I arrived at the house, it was little more than a shack in the woods, and I assumed I had wasted my time—but inside I discovered almost 6000 volumes, including a huge collection of modern first editions in their original dust jackets. The deceased had not been a book collector per se, he had just bought all the important works of mid 20th century literature as they were published and kept them in perfect condition. I was able to buy the bulk of the collection, and when sorting through these books, I was on the verge of tossing a pair of paperback volumes into the 25¢ pile when luckily, I had second thoughts. It turned out the volumes were the first printing of Nabokov’s Lolita. After I sold them to another dealer I later saw the same pair catalogued for $3000. Of course such stories are the exception rather than the rule—as Peter Byerly says, dealing in rare books is not a get rich quick scheme—but the excitement of the treasure hunt was part of what I loved about being an antiquarian bookseller.